Freedom is never free. Anyone who has struggled to be free knows how much it costs.

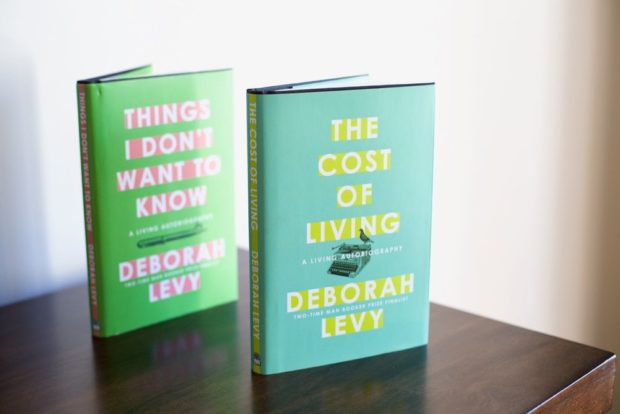

Deborah Levy is in my head. Playwright, novelist, poet: Levy has worked in many genres and has twice been shortlisted for the Man Booker prize. I have just read the first two of what she calls her living memoir. She isn’t the first writer to do this nor will she be the last. Still, there is something in the reckoning of the age; in the gathering of her life as she dismantles and builds again; yes, something has caught me in the here and now.

Because of this:

Perhaps when Orwell described sheer egoism as a necessary quality for a writer, he was not thinking about the sheer egoism of a female writer. Even the most arrogant female writer has to work overtime to build an ego that is robust enough to get her through January, never mind all the way to December.

and this:

When we kissed, I knew we were both in the middle of some sort of catastrophe and I didn’t know if something was starting or if it was stopping.

and this:

We were on the run from the lies concealed in the language of politics, from myths about our character and our purpose in life. We were on the run from our own desires too probably, whatever they were. It was to best to laugh it off. The way we laugh. At our own desires. The way we mock ourselves. Before anyone else can. The way we are wired to kill. Ourselves.

Levy was born in South Africa in 1959 and moved to Britain in 1986 with her family. Her parents divorced eight years later.; all detailed in these memoirs with stunning clarity.

As my tears dripped on to Sister Joan’s holy veil, I thought about how she had shaved off her hair, which she called her weeds of ignorance. She had told me to say my thoughts out loud but I had tried writing them down instead. Sometimes I showed her what I had written and she always made time to read everything. She said I should have told her I could read and write. Why hadn’t I told her? I said I didn’t know, and she said I shouldn’t be scared of something ‘transcendental’ like reading and writing. She was on to something because there was a part of me that was scared of the power of writing. Transcendental meant ‘beyond’, and if could write beyond, whatever that meant, I could escape to somewhere better than where I was now.

Autumn is time for juicy dense work so perhaps these slim volumes will disappear in my head among the other hot titles on my reading shelf. These are not the stuff of burrowing by the fire to travel as the flames flicker. They are lightening rods, as the best kind of writing is, both personal and political. These are the books you lend out to all your friends as it’s all of our stories, in part, in full, in tone and nuance, in fury, and wonder too, in the culture we inhabit.

Chaos is what we most fear but I have come to believe it might be what we most want.